The recent overhaul of India’s criminal justice system, culminating in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) of 2023, was presented as a landmark step in decolonizing the law.

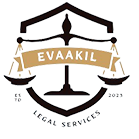

However, a close examination of Section 74 of the BNS, which replaces the controversial Section 354 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) concerning ‘outraging the modesty of a woman,’ reveals a different story. This article argues that the new provision, while symbolically repackaged, represents a significant missed opportunity for substantive reform.

By retaining the archaic and undefined concept of ‘modesty’ and simply carrying forward the post-2013 penalty structure, the BNS fails to transition from a colonial-patriarchal framework to one centered on the constitutional rights of dignity and bodily autonomy.

From IPC §354 to BNS §74

A deep dive into the law on outraging modesty. Is the new Sanhita a genuine reform or just a renumbering exercise?

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, has replaced the colonial-era Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, aiming to decolonize and modernize India's legal framework. A key provision is Section 74 of the BNS, which succeeds Section 354 of the IPC on "assault or criminal force to woman with intent to outrage her modesty."

While this appears to be a simple renumbering, a closer look reveals a story of legislative continuity, not revolution. This analysis argues that by retaining the jurisprudentially contentious and archaic concept of 'modesty,' the BNS has perpetuated a colonial-patriarchal understanding of sexual violence, representing a significant missed opportunity for the substantive, rights-based reform that was its stated objective.

At a Glance: IPC vs. BNS

The core definition of the offense remains identical. This comprehensive table breaks down the key legal and procedural attributes of the provision across its legislative evolution, revealing that the most significant changes occurred in 2013, with the BNS adopting this amended framework wholesale.

| Feature | IPC §354 (Pre-2013) | IPC §354 (Post-2013) | BNS §74 (2023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment | Imprisonment up to 2 years, or with fine, or with both. | 1 to 5 years imprisonment + fine (Mandatory Minimum) | 1 to 5 years imprisonment + fine (No Change) |

| Bailability | Bailable | Non-bailable | Non-bailable |

| Cognizability | Cognizable | Cognizable | Cognizable |

| Compoundability | Non-compoundable | Non-compoundable | Non-compoundable |

| Triable By | Any Magistrate | Any Magistrate | Any Magistrate |

| Placement in Code | Chapter XVI (Offences Affecting the Human Body) | Chapter XVI (Offences Affecting the Human Body) | Chapter V (Offences Against Woman and Child) |

Infographic: A Symbolic Structural Shift

One of the most praised changes in the BNS is the reorganization of offenses. Crimes against women and children are no longer scattered but are consolidated into a dedicated chapter, Chapter V. While a positive symbolic gesture, it stands in contrast to the lack of substantive change within the provision itself.

Indian Penal Code (IPC)

Offenses were dispersed

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

Consolidated into a single chapter

Chapter V: Offences Against Woman and Child

§74: Outraging Modesty

§75: Sexual Harassment

§76: Assault to Disrobe

§77: Voyeurism

§78: Stalking

Legislative Timeline

The law against outraging modesty has evolved significantly over 160+ years. The timeline below highlights the key milestones.

1860

IPC Enacted

Section 354 is introduced. The punishment is discretionary: up to 2 years, a fine, or both. The offense is bailable.

2013

Criminal Law (Amendment) Act

In the aftermath of the 2012 Delhi gang-rape case, the law is made much stricter. A mandatory minimum sentence of 1 year (extendable to 5) is introduced, and the offense becomes non-bailable.

2013

Justice Verma Committee Report

A missed opportunity. The committee recommends replacing the term 'outraging modesty' with 'sexual assault' to move from a morality-based to a rights-based framework. The legislature does not adopt this.

2023

BNS Enacted

BNS Section 74 is introduced. It carries forward the exact text and the stricter, post-2013 punishment structure of IPC Section 354. The law is substantively the same, just renumbered and repositioned.

The Enduring Problem of 'Modesty'

The Elusive Definition: 'Modesty' as a Judicial Construct

A core challenge in applying both IPC §354 and BNS §74 is the term 'modesty' itself. Neither statute provides a definition, delegating this task to the judiciary. This has made 'modesty' a fluid legal construct, shaped by evolving societal norms and described by courts as a "womanly propriety of behaviour" tied to a woman's gender.

Landmark Cases Shaping the Law

The legal understanding of "outraging modesty" rests on a foundation of landmark judicial pronouncements that remain fully applicable under the BNS.

State of Punjab v. Major Singh (1967)

The Supreme Court held that modesty is an attribute a female possesses from birth, regardless of her age or her own understanding. The focus is on the accused's intent, not the victim's reaction.

Rupan Deol Bajaj v. K.P.S. Gill (1995)

Introduced the "reasonable woman" test. The act is judged based on whether a reasonable person would consider it an outrage to a woman's modesty.

Ramkripal v. State of M.P. (2007)

The Court powerfully stated that "the essence of a woman's modesty is her sex." This broadens the scope to any act that demeans a woman because of her gender.

A Missed Opportunity for Reform

The Justice Verma Committee recommended replacing the colonial concept of 'modesty' with the rights-based term 'sexual assault'. This would have shifted the focus from a woman's 'virtue' to the violation of her bodily autonomy and dignity. The BNS's failure to adopt this recommendation means it perpetuates an archaic legal framework.

The Unbroken Chain of Precedent

A critical practical implication is that the entire body of judicial precedent established under IPC §354 remains directly applicable to BNS §74. Because the text is identical, the interpretations from cases like *Major Singh* continue to be the governing law. This provides legal stability but also ensures that the jurisprudential baggage of 'modesty' is carried forward into the new legal regime, locking in the old framework.

Analysis: The Sentencing Paradox

It is crucial to note that the significant enhancement in punishment for this offense was not an innovation of the BNS. It was the result of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013. The BNS simply adopts this post-2013 structure. This allows for an evidence-based analysis of a policy that has been in effect for over a decade.

The 2013 amendment introduced harsher, mandatory minimum sentences to deter crime. However, legal experts and data suggest this can have an unintended consequence: the "sentencing paradox."

Interactive Chart: Stricter Laws vs. Conviction Rates

Filter by Offense:

Note: Data is illustrative. The rape data reflects findings from a Delhi trial court study showing a conviction rate drop from 16.1% (pre-2013) to 5.7% (post-2013).

Why does this happen?

When faced with a rigid mandatory sentence, judges may become more hesitant to convict in borderline cases. If they feel the punishment is disproportionate to the act, they might lean towards acquittal. For example, one academic study on rape cases in Delhi found a stark decline in the conviction rate from 16.11% under the older, more discretionary law to just 5.72% under the amended, stricter law. This suggests tougher laws don't always lead to more convictions.

What's More Effective? Procedural Reform

The real impact on justice may not come from harsher sentences, but from better procedures. The new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) introduces reforms like e-FIRs, strict investigation timelines, and witness protection. Experts argue that the certainty and swiftness of punishment are a more powerful deterrent than its severity.

Conclusion & Recommendations

Synthesis of Findings

This analysis concludes that BNS §74 is a direct continuation of the post-2013 version of IPC §354. The BNS's primary failure was its refusal to adopt the Justice Verma Committee's recommendation to replace 'modesty' with 'sexual assault,' thus missing a key opportunity for decolonization. The stricter sentencing, inherited from the 2013 amendment, must be viewed critically due to the "sentencing paradox," where judicial reluctance to impose rigid penalties may lead to lower conviction rates.

For the Legislature

Amend BNS §74. Replace "outraging modesty" with "sexual assault" to ground the law in the constitutional right to dignity and bodily autonomy, as recommended by the Justice Verma Committee.

For the Judiciary

Continue to interpret 'modesty' progressively through the lens of Article 21. Center the victim's right to dignity, not archaic notions of her character.

For Policy Makers

Focus on implementing the procedural reforms in the BNSS. Swift investigations, better evidence collection, and fast-track courts are the key to effective deterrence and justice.