Spousal property rights in India sit at the crossroads of religion-based personal laws, evolving civil statutes, and a wave of recent reforms such as Uttarakhand’s Uniform Civil Code.

This guide unpacks how ownership and control of assets shift during marriage, divorce, maintenance proceedings, and succession—covering Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Special Marriage Act frameworks as well as live-in relationships, NRIs, and benami transactions.

Whether you are safeguarding stridhan, negotiating alimony, or planning an estate, the article distils current statutes and landmark judgments into plain-English rules, plus practical check-lists for equitable settlements.

Spousal Property Rights in India: A Comprehensive Guide

An in-depth analysis of husband's and wife's claims across legal frameworks.

I. Introduction: The Multi-Faceted Landscape of Indian Property Law

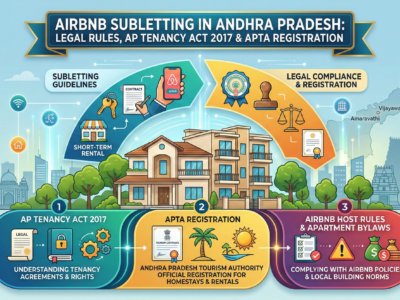

India's legal framework governing family and property matters is characterized by its intricate diversity, primarily operating under a system of personal laws. These laws, rooted in religious scriptures and traditions, dictate the specific rights and obligations of spouses concerning property, leading to significant variations based on an individual's religious affiliation or the nature of their marriage.

A. Overview of Personal Laws and the Special Marriage Act

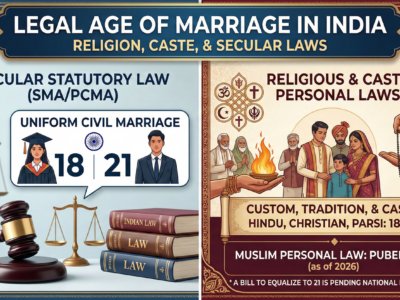

The legal landscape is broadly categorized by distinct personal laws and a secular civil code. Hindu Law, applicable to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains, is primarily governed by the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, for marital matters and the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, for property and inheritance rights.

For Muslims, the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, and the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939, regulate marriage and inheritance.

Christians in India are subject to the Indian Divorce Act, 1869, for divorce proceedings and the Indian Succession Act, 1925, for inheritance.

Beyond these religion-specific frameworks, the Special Marriage Act, 1954, offers a secular alternative for inter-religious couples or those preferring a civil marriage, irrespective of their faith. Under this Act, property division generally adheres to general civil laws. Inheritance for couples married under the Special Marriage Act is typically governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, unless both parties identify as Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, or Jain, in which case the Hindu Succession Act applies. This layered legal structure necessitates a nuanced understanding of property rights, as the applicable law directly shapes entitlements and obligations.

B. Key Property Classifications: Self-Acquired, Ancestral/Inherited, Jointly Owned, and Stridhan/Mehr

A precise categorization of property is fundamental to discerning spousal rights, as each type carries distinct legal implications.

- Self-Acquired Property: Assets obtained by an individual spouse either before marriage or acquired during marriage through their own earnings, efforts, or from sources unrelated to marital contributions.

- Ancestral/Inherited Property: Property received as an inheritance. In Hindu law, it's undivided property held by four generations of male lineage. Muslim law doesn't differentiate.

- Jointly Owned Property (Marital Property): Assets acquired by both spouses during their marriage through joint financial contributions or collective efforts.

- Stridhan (Hindu Law) and Mehr (Muslim Law): Crucial and unique categories of property primarily designated for women, providing financial independence. Stridhan is a Hindu woman's absolute property (gifts, valuables). Mehr is a mandatory payment from a Muslim husband at marriage.

C. Core Principles Governing Property Division in India (Equitable vs. Equal Distribution)

India's legal approach to property division, particularly in the context of marital dissolution, differs significantly from "community property" systems. The Indian legal system generally adheres to a "separate property" regime, meaning property ownership is primarily determined by who holds the legal title and who made the financial contributions. Courts in India do not mandate an automatic 50:50 division of property upon divorce. Instead, the guiding principle is "equitable distribution," aiming for a fair outcome considering specific circumstances.

Equitable vs. Equal Distribution in India

Equitable Distribution

Fair division based on circumstances, contributions (financial & non-financial), duration of marriage, and future needs.

(Indian Legal System)

Equal Distribution (e.g., 50:50)

Automatic division of marital assets, regardless of individual contributions.

(Community Property Regimes)

This infographic illustrates the fundamental difference in property division principles.

II. Property Rights During Marriage: Ownership and Control

During the subsistence of a marriage, the ownership and control of property are subject to distinct rules depending on the type of property and the gender of the spouse.

A. Husband's Rights on Wife's Property

A husband generally possesses limited or no direct ownership rights over his wife's individual property during the marriage. The law strongly protects a woman's separate assets.

- Self-Acquired Property of Wife: Any property purchased or acquired by the wife in her own name, whether before or during the marriage, remains her exclusive self-acquired property. A husband cannot assert any legal claim over such property during the marriage unless he can definitively prove his monetary contribution was intended as a joint investment, or if the property is jointly titled in both names.

- Inherited Property of Wife: Property inherited by the wife from her parents or other relatives is unequivocally treated as her individual property. The husband generally has no claim over such assets, as they are considered her exclusive ownership.

- Jointly Owned Property with Wife: If a property is legally registered in both spouses' names, both parties possess legal rights over it. In such cases, the husband can claim a share based on his financial contribution and the legal ownership documents.

- Stridhan/Mehr of Wife: Stridhan (for Hindu women) and Mehr (for Muslim women) represent absolute property rights for the wife, offering significant financial security and independence. This legal structure reveals a distinct asymmetry in the protection of individual property rights. The robust protection of Stridhan and Mehr serves as a crucial mechanism to provide women with a secure financial base, independent of their husband's control, thereby mitigating their economic vulnerability. This is not necessarily a "bias" but a protective measure designed to address pre-existing societal inequalities. If the husband or his relatives misappropriate or withhold Stridhan, they can be held criminally liable under laws like Section 406 of the Indian Penal Code (criminal breach of trust).

B. Wife's Rights on Husband's Property

During the subsistence of marriage, a wife's rights over her husband's property are primarily centered on maintenance and the right to residence, rather than direct ownership, unless the property is jointly owned or she has made demonstrable financial contributions.

- Self-Acquired Property of Husband: A wife generally cannot claim a direct share or ownership in her husband's self-acquired property during his lifetime, unless the property is jointly owned or she can prove financial contribution to its acquisition. However, a significant right for the wife is her entitlement to reside in the matrimonial home, even if it is solely in her husband's name.

- Ancestral Property of Husband: Under Hindu law, a wife generally does not possess a direct right to her husband's ancestral property during his lifetime, primarily because she is not considered a "coparcener" by birth in the Hindu Joint Family. However, if the ancestral property undergoes a partition and the husband receives his share, that portion then transforms into his "separate property." In such a scenario, the wife may have a claim to this partitioned share upon his death, particularly if he dies intestate (without a will).

- Jointly Owned Property with Husband: When a property is jointly owned by both spouses, and both have contributed financially to its acquisition, courts typically evaluate the extent of each party's contributions to determine a proportional division. Even in cases where the property is titled in both names but only one spouse made the financial contributions, the non-contributing spouse may still assert a claim, especially if they can demonstrate significant non-financial contributions (e.g., household management, childcare) that indirectly supported the acquisition or maintenance of the property.

Spousal Property Rights During Marriage: A Snapshot

Husband's Rights on Wife's Property

- Self-Acquired: No Claim (unless joint investment/title)

- Inherited: No Claim

- Jointly Owned: Claim based on Contribution

- Stridhan/Mehr: No Claim (Absolute Ownership by Wife)

Wife's Rights on Husband's Property

- Self-Acquired: No Direct Ownership Claim (Right to Residence)

- Ancestral: No Direct Coparcenary Right (Potential claim on partitioned share upon death)

- Jointly Owned: Claim based on Contribution (Financial & Non-Financial)

- Stridhan/Mehr: N/A (Wife's exclusive property)

This infographic provides a simplified overview of common claims during marriage. Specifics depend on individual case facts and legal interpretation.

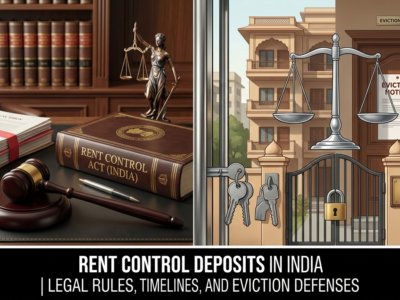

III. Property Rights Upon Dissolution of Marriage (Divorce/Separation)

Upon the dissolution of marriage in India, the division of property is a complex process guided by principles that prioritize fairness over strict equality.

A. General Principles of Property Division in Divorce

Indian law does not mandate an automatic 50:50 division of property between spouses upon divorce. Instead, courts aim for an "equitable distribution," meaning a fair division based on the specific circumstances of the case, rather than a mathematically equal split. Property ownership is primarily determined by legal title deeds and ownership records. Assets acquired during the marriage are typically considered "marital property" and are subject to division. Conversely, assets owned by a spouse before marriage or received as individual gifts or inheritance during the marriage are generally treated as "separate property" and remain with the original owner.

B. Under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 & Hindu Succession Act, 1956

- Self-Acquired Property: A wife generally cannot claim a share in her husband's self-acquired property after divorce, unless the property was jointly owned or she can prove direct financial contribution to its acquisition. Conversely, the husband also cannot claim the wife's self-acquired property.

- Ancestral Property: A divorced wife explicitly loses her claim to the husband's ancestral property. However, children from the marriage retain their inheritance rights to ancestral property.

- Jointly Owned Property: If a property is jointly owned by both spouses and both contributed financially, the court will typically evaluate the proportion of each party's contributions to determine the division.

- Stridhan: The wife retains an inalienable and absolute right over her Stridhan. This property remains hers even after divorce or judicial separation. The husband or his in-laws are legally considered trustees of her Stridhan and are bound to return it upon demand. Misappropriation or refusal to return Stridhan can lead to criminal liability under Section 406 of the Indian Penal Code.

- Right to Residence in Matrimonial Home: A divorced wife can claim residence rights in the matrimonial home under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA), but this right largely ceases once divorce is final unless linked to a domestic-violence cause-of-action that occurred while the marriage was subsisting. She may be granted alimony or alternative accommodation instead of permanent residence in the husband's house.

C. Under Muslim Personal Law

- Self-Acquired and Inherited Property: Muslim personal law does not distinguish between self-acquired and ancestral property for inheritance purposes; all property is considered heritable upon death. However, upon divorce, there is generally no automatic claim over the ex-husband's individually owned property. Each spouse typically retains property acquired in their individual names.

- Jointly Owned Property: Division is governed by the title deed or by proving a beneficial interest (trust). Muslim law does not recognize community property.

- Mehr and Maintenance: A Muslim wife is entitled to Mehr, which is her absolute property, as a fundamental right. Post-divorce, a Muslim husband is legally obligated to make a reasonable and fair provision for the future of the divorced wife, which explicitly includes her maintenance, and this liability can extend beyond the 'iddat' (waiting) period (post-Danial Latifi).

D. Under the Indian Divorce Act, 1869 (for Christians) & Indian Succession Act, 1925

- Self-Acquired and Inherited Property: A Christian wife has no automatic claim over her ex-husband's individually owned property after divorce. Property division generally adheres to the principle of ownership. Similarly, a husband cannot claim the wife's self-acquired or inherited property.

- Jointly Owned Property: Jointly owned property is subject to equitable distribution, taking into account factors such as financial contributions, the duration of the marriage, and the future needs of each spouse.

- Alimony and Maintenance: The court has the discretion to grant alimony to a Christian wife under Section 37 of the Indian Divorce Act, 1869, particularly if she demonstrates an inability to sustain herself financially post-divorce.

E. Under the Special Marriage Act, 1954

- Property Division Principles: For couples married under the Special Marriage Act, property division generally follows general civil laws. The Act specifically allows courts to decide on the disposal of property that was jointly acquired during the marriage.

- Alimony and Maintenance: Sections 36 and 37 of the Special Marriage Act empower the court to grant alimony and maintenance to a spouse, but these provisions do not automatically confer a share in the other spouse's property.

F. The Role of Financial and Non-Financial Contributions in Property Division

Indian courts, in their pursuit of equitable distribution, consider a broad range of contributions. Courts evaluate both direct financial contributions (such as income earned, investments made, mortgage payments, and expenses incurred in property upkeep) and, to a certain extent, indirect or non-financial contributions (including homemaking, raising children, and providing support for the other spouse's career or business endeavors) when determining asset division and alimony. This trend has been affirmed by Supreme Court and multiple High Court rulings (e.g., the May 2025 SC alimony case involving house transfer).

Table 1: Factors Influencing Property Division in Divorce (Across Religions/Acts)

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Duration of Marriage | Longer marriages often lead to more equitable divisions due to collaborative efforts and financial interdependence over time. |

| Financial Contributions | Direct monetary contributions by each spouse towards acquisition, maintenance, or improvement of assets. |

| Non-Financial Contributions | Indirect contributions such as homemaking, childcare, and supporting the other spouse's career or business endeavors. These significantly influence alimony and overall settlements. |

| Future Financial Needs & Earning Capacity | Assessment of each spouse's ability to support themselves post-divorce, considering their age, health, qualifications, and employment prospects. |

| Value of Shared Assets | The total worth of all marital property subject to division. |

| Custody & Welfare of Minor Children | The needs of dependent children, including their living arrangements and financial support, often influence property and maintenance decisions. |

| Standard of Living During Marriage | Courts aim to ensure that the dependent spouse can maintain a lifestyle similar to what they enjoyed during the marriage. |

| Conduct During Marriage | In contested divorce cases, the behavior of both spouses (e.g., abuse, fraud) can influence the court's discretion in property division and alimony. |

| Status of Property | Distinction between self-acquired property (generally retained by owner) and jointly owned property (subject to division). |

| Legal Expenses for Dependent Spouse | Courts may consider the legal costs incurred by a financially dependent spouse in seeking a fair settlement. |

IV. Alimony and Maintenance: Financial Support Post-Divorce

Financial support mechanisms, broadly categorized as alimony and maintenance, are critical components of divorce settlements in India, designed to ensure the economic stability of the dependent spouse.

A. Distinction Between Alimony and Maintenance

While the terms "alimony" and "maintenance" are often used interchangeably in common parlance, they possess nuanced legal distinctions in India. Maintenance generally refers to financial support provided during the subsistence of a marriage when spouses are living separately, during the pendency of a matrimonial case (interim maintenance), or as periodic payments after a divorce or judicial separation. Its purpose is to provide for the basic needs and livelihood of the dependent spouse and children, ensuring they are not left destitute. Alimony, on the other hand, is typically awarded after the divorce proceedings have concluded, often as a one-time lump-sum payment or a series of regular payments. While both aim to address economic disparities and ensure financial justice, maintenance focuses on ongoing sustenance, whereas alimony often represents a final financial settlement. The entitlement to maintenance is predicated on the claimant not having sufficient means to support themselves.

B. Factors Influencing Alimony/Maintenance Calculation

The determination of alimony or maintenance amounts is not based on a fixed formula but is highly discretionary, with courts considering various factors to arrive at a fair and just sum:

- Income and Earning Capacity of Both Spouses: Paramount consideration. Higher income spouse generally provides support.

- Duration of Marriage: Longer marriages tend to result in greater awards.

- Age and Health: Crucial for determining lifelong support needs.

- Child Custody and Caregiving Responsibilities: Influences overall financial support.

- Standard of Living During Marriage: Courts aim to maintain a similar lifestyle for the dependent spouse.

- Conduct During Marriage: Can influence court's decision in contested cases.

Conceptual Alimony/Maintenance Impact Factors

This conceptual bar chart illustrates the relative impact of various factors on alimony/maintenance amounts. (Height represents impact level)

C. Husband's Right to Claim Alimony/Maintenance from Wife

While less common, Indian law allows a husband to claim alimony/maintenance from his wife under specific conditions, such as financial dependency due to disability and the wife having a significantly higher income. Sections 24 & 25 of the Hindu Marriage Act and several High Courts allow this if the wife's income is higher. This reflects a move towards gender-neutrality in maintenance law.

D. Enforcement of Maintenance Orders

Maintenance orders can be enforced through various legal mechanisms. If a person fails to comply with a court order for maintenance, the Magistrate can issue a warrant for levying the amount due, similar to levying fines, and may even sentence the person for non-compliance. In cases of last resort, the court can strike off the defense of the respondent. This ensures that financial support mandated by the court is provided to the dependent spouse and children.

V. Property Rights Upon Death (Inheritance)

The devolution of property upon the death of a spouse is governed by specific inheritance laws, which vary significantly based on the deceased's religion and whether they left a valid will.

A. Hindu Succession Act, 1956

- Wife's Inheritance Rights (Widow): Entitled to an equal share of husband's property (self-acquired and partitioned ancestral) along with children if he dies intestate.

- Husband's Inheritance Rights (Widower): Inherits wife's property along with children if she dies intestate.

- Children's Inheritance Rights: Retain inheritance rights to ancestral property. Daughters are coparceners. Equal share in father's self-acquired property if he dies intestate.

B. Muslim Personal Law

- Wife's Inheritance Rights (Widow): A childless widow is entitled to one-fourth (1/4) of her deceased husband's property after funeral expenses, legal costs, and debts are met. If there are children or grandchildren, her share reduces to one-eighth (1/8). If the deceased husband had more than one wife, the one-eighth share is divided equally among them.

- Husband's Inheritance Rights (Widower): A widower (husband) receives half (1/2) of his deceased wife's property if they have no children. With children, the husband's share decreases to one-fourth (1/4).

- Children's Inheritance Rights: Children's shares in inheritance follow specific principles: a sole daughter inherits half (1/2) of the estate, while multiple daughters collectively inherit two-thirds (2/3). A son generally gets double the share of a daughter wherever they jointly inherit.

C. Indian Succession Act, 1925 (for Christians)

- Wife's Inheritance Rights (Widow): Upon her husband's death, a Christian widow can inherit one-third (1/3) of his property, with the children receiving the remaining shares. If there are no children, she receives half (1/2) of his property. The previous minimum cap of ₹5,000 was removed in the 2002 amendment.

- Husband's Inheritance Rights (Widower): If a Christian wife dies without a will, her property is inherited by her husband and children. If there are no surviving children, the husband is entitled to the entire property.

- Children's Inheritance Rights: A daughter in a Christian family typically receives an equal share of her parental properties along with her siblings. The Indian Succession Act states that if a father dies intestate, the property will be inherited by the children of the deceased, meaning both sons and daughters are entitled to get the property.

D. Impact of Wills (Testamentary Succession) vs. Intestate Succession

The existence of a valid will (testamentary succession) significantly alters the distribution of property compared to intestate succession (dying without a will). For self-acquired property, a person has the right to dispose of it as they wish through a will, overriding the default rules of inheritance. If a will exists, the property will be distributed according to its provisions, potentially disinheriting legal heirs who would otherwise have a claim under intestate succession.

For ancestral property, the situation is more complex. While a will cannot typically divert ancestral property that is undivided, if the ancestral property is partitioned and a spouse receives their share, that share transforms into their self-acquired property, which they can then bequeath through a will. This distinction is crucial, as it determines the extent to which an individual can control the post-mortem distribution of their assets.

Inheritance Shares Upon Death (Intestate Succession)

Hindu Succession Act, 1956

Muslim Personal Law

Indian Succession Act, 1925 (Christians)

This infographic provides a general overview of intestate inheritance shares. Specifics can vary based on additional heirs and legal interpretations.

VI. Special Scenarios and Emerging Legal Developments

Beyond the established personal laws, several specific scenarios and recent legal developments introduce further complexities and changes to spousal property rights in India.

Filter Legal Scenarios

(This filter is conceptual and would dynamically show/hide sections in a real application.)

A. Property Registered in Spouse's Name, Paid by Other Spouse (Benami Transactions)

It is a common practice for a husband to purchase property in his wife's name, or jointly with her, often out of love and affection, or to avail benefits such as reduced stamp duty or tax advantages. In such instances, the husband may pay the entire consideration, even if the wife does not contribute financially.

The legal implications of such transactions are governed by the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988. This Act generally prohibits the recovery of property held benami, meaning property held in one person's name but financed by another without the intention of transferring beneficial interest. However, a crucial exception exists under Section 2 (9) A(iii) of the Act, which allows a person to claim title over property purchased in the name of their spouse or child, provided the consideration was paid from the individual's known sources. The Calcutta High Court in 2023 confirmed that the burden of proof lies with the claimant.

In cases of matrimonial dispute, if a property is registered in the wife's name but fully paid for by the husband, courts will investigate the beneficial ownership and the intent behind the transaction. If the husband can prove that the payment came from his known sources and it was not intended as an absolute gift without any beneficial interest retention, he may be able to assert a claim, although this can be challenging to prove. The Supreme Court has reiterated that self-acquired property of a spouse cannot be claimed by the other unless there is clear evidence of joint ownership or financial contribution.

B. Live-in Relationships and Property Rights

In India, there is no specific legislation governing live-in relationships, which means they lack a formal legal framework for property rights akin to marriage. However, the Supreme Court of India has, through various judgments, recognized these relationships as a form of companionship, sometimes akin to marriage, granting limited rights to partners, particularly women and children.

Maintenance: A woman in a live-in relationship can seek maintenance under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA), and in some cases, under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. For maintenance claims to be valid, the relationship must meet certain criteria, such as the couple holding themselves out to society as married, being of legal age to marry, being unmarried and legally eligible, and cohabiting voluntarily for a significant period, presenting themselves as partners.

Property Rights: Generally, partners in a live-in relationship do not have automatic inheritance or property rights over each other's assets. However, if both partners contribute to the acquisition of an asset or property, they may claim joint ownership or an equitable share in it, provided they can show significant contribution. Children born out of live-in relationships are considered legitimate and are entitled to all rights as lawful offspring, including inheritance rights over their parents' property.

The Uttarakhand Uniform Civil Code (UCC) has made it mandatory for live-in relationships to be registered, with penalties for non-compliance or false information. This registration is primarily for record-keeping and does not alter the legal standing of the partners, though it aims to ensure an official record exists.

C. Uniform Civil Code (UCC) - Uttarakhand Model

Uttarakhand has become the first Indian state to implement a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), aiming to standardize personal laws for all citizens regardless of their religion, covering aspects like marriage, divorce, property, and inheritance. Notably, Scheduled Tribes are explicitly excluded from its purview to protect their traditional rights.

Impact on Property Rights: The Uttarakhand UCC introduces significant changes to inheritance laws:

- For Hindus: It eliminates the traditional distinction between self-acquired and ancestral property. Under the UCC, all legitimate heirs will be entitled to ancestral property in the same way they are to self-acquired property. It also recognizes both parents (mother and father) as Class-I heirs in intestate succession, a departure from the Hindu Succession Act where the father is a Class-II heir if the deceased is a Hindu male.

- For Muslims: The UCC abolishes the principle of fixed shares in intestate succession, which often disproportionately benefited male heirs, and instead grants Muslim women the same property rights as Muslim men in such cases. However, the Shariat law's restriction on bequeathing only one-third of property through a will remains in the enacted Uttarakhand Bill.

- For Christians: While the Indian Succession Act already provides relatively liberal inheritance laws, the UCC standardizes the framework further, aligning it with the principle of equal rights for all citizens.

The implementation of the UCC is lauded by proponents as a measure for women's empowerment and gender equality, aiming to end practices like polygamy, child marriage, and triple talaq. However, critics raise concerns about its potential to disproportionately impact Muslim personal law practices and religious freedom, viewing it as a "majoritarian code" rather than a truly uniform one. The UCC's retrospective application for marriage registration and penalties for non-compliance also raise concerns about individual liberties.

D. Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) and Property Rights

Divorce and property division for Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) involve complexities due to jurisdictional issues and the interplay of Indian and foreign laws.

Jurisdiction: Indian courts retain jurisdiction for divorce cases if the marriage was solemnized under Indian laws (e.g., Hindu Marriage Act, Special Marriage Act) or if either party has a clear connection with the Indian jurisdiction (e.g., last resided together in India, or one spouse currently resides in India). Physical presence of both parties in India may not always be necessary, with provisions for representation through power of attorney or video conferencing.

Property Division: For properties located within India, Indian courts can adjudicate disputes. Foreign assets, however, typically fall under the jurisdiction of the country of residence. Property division for NRIs is based on mutual agreement in consent divorces or court orders in contested cases, considering each party's contributions and the welfare of any children. Full disclosure of all assets, including those held abroad, is usually required.

Inheritance: NRIs can inherit immovable property in India from both Indian residents and other non-residents, and there are generally no limitations on the types of property they can inherit (residential, commercial, agricultural, including farmhouses), subject to Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) regulations. India does not levy an inheritance or estate tax, so NRIs do not incur direct tax liabilities upon inheriting property. However, compliance with FEMA regulations for property transfers and potential capital gains tax upon the sale of inherited property is necessary.

Challenges: NRIs often face logistical challenges in attending hearings, ensuring recognition of foreign divorce decrees (which Indian courts may refuse if they violate natural justice or Indian law), and navigating compliance with Indian tax and foreign exchange laws. Seeking professional legal advice is highly recommended for NRIs to navigate these complexities effectively.

VII. Conclusion: Key Takeaways and Future Outlook

Navigating spousal property rights in India requires understanding its intricate legal frameworks, primarily driven by diverse personal laws and evolving judicial interpretations. Here are the key takeaways:

- Separate Property Regime: India operates on a "separate property" system, where ownership is based on legal title and financial contribution, not an automatic 50:50 split upon marriage or divorce. Courts aim for "equitable distribution" based on individual circumstances.

- Wife's Protected Assets: "Stridhan" (Hindu law) and "Mehr" (Muslim law) are the wife's absolute and inalienable properties, offering crucial financial independence and criminal protection against misappropriation.

- Wife's Rights on Husband's Property: While a wife generally doesn't get direct ownership of her husband's self-acquired or ancestral property during his lifetime or upon divorce, she has significant rights to maintenance, alimony, and a crucial right to residence in the matrimonial home (even if not an owner), especially under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. This right largely ceases once divorce is final unless linked to a domestic-violence cause-of-action that occurred while the marriage was subsisting.

- Husband's Rights on Wife's Property: A husband typically has no claim over his wife's self-acquired, inherited, or Stridhan/Mehr properties. In jointly owned property, division is based on financial contributions. Husbands can claim maintenance from wives if financially dependent and the wife has significantly higher income.

- Recognition of Non-Financial Contributions: Courts increasingly consider non-financial contributions (homemaking, childcare) when determining alimony and overall financial settlements, reflecting a progressive recognition of their economic value in marital partnerships.

- Emerging Legal Landscape (UCC): The Uniform Civil Code (UCC), exemplified by Uttarakhand's model, signals a shift towards greater uniformity and gender equality in property and inheritance laws, particularly impacting Hindu and Muslim personal laws by abolishing distinctions and modifying inheritance shares. However, the 1/3rd testamentary cap for Muslims remains in the enacted Uttarakhand Bill. These changes, while aiming for empowerment, also raise complex questions about religious freedom.

The highly case-specific nature of property disputes, coupled with the interplay of personal laws, civil statutes, and judicial precedents, underscores the imperative for individuals to seek expert legal counsel to protect their interests and ensure just outcomes.

Summary of Key Takeaways

| Aspect | Key Principle |

|---|---|

| Property Division | Equitable, not 50:50. Based on title & contributions. |

| Wife's Exclusive Property | Stridhan/Mehr are absolute; husband has no claim. |

| Wife's Rights on Husband's Property | No direct ownership (unless joint), but right to residence & maintenance. |

| Husband's Rights on Wife's Property | No claim on wife's self-acquired/inherited/Stridhan/Mehr. Can claim maintenance if dependent. |

| Non-Financial Contributions | Increasingly considered for alimony/settlements. |

| UCC Impact | Aims for uniformity & gender equality in property/inheritance. |