Managing a WhatsApp group in India? You’ve likely wondered about your legal responsibility for messages posted by members. The fear of being held liable for someone else’s content is a major concern for millions of administrators. This comprehensive guide from eVaakil.com demystifies the law, explaining the crucial court rulings that protect admins from vicarious liability. We’ll break down the “common intention” test, your duties under the IT Act, and provide actionable best practices to keep your group safe and legally compliant.

Juridical Analysis

The Legal Liability of WhatsApp Group Administrators in India

A comprehensive guide to the rights, responsibilities, and risks for admins in the evolving digital landscape.

Executive Summary

The settled legal position in India is that a WhatsApp group administrator cannot be held vicariously liable for objectionable content posted by a group member. Liability can only be attached if a "common intention" or "pre-arranged plan" between the admin and the member is proven. This report dissects the judicial precedents and provides actionable best practices for responsible group administration.

I. The Admin's Role: A Technical & Legal Primer

Understanding an admin's role is foundational. The Indian judiciary has focused on the technical realities of this position to build a legal framework that resists broad, status-based liability.

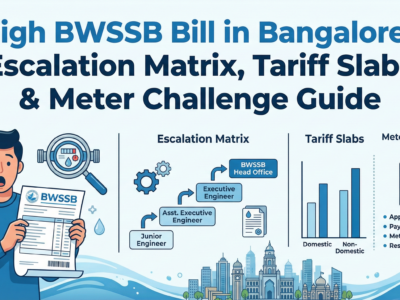

Admin Powers: Perception vs. Reality

Courts recognize that an admin's technical ability to control content is limited, which is a cornerstone of legal protection against vicarious liability.

Perception

- Censor Posts

- Pre-Approve Media

- Edit Member Messages

Reality

- Add Members

- Remove Members

- Change Group Info

The "Default Admin" Danger

A legally precarious scenario is that of the "default admin," where a member is automatically assigned admin privileges after the previous admin exits. This passive acquisition of status highlights the potential for injustice if liability were attached merely to the title. Cases where individuals became admins by default and faced charges for content they did not post, such as the Junaid Khan case involving sedition charges, underscore the importance of the judiciary's focus on intent over mere status.

II. Foundational Legal Principles: Direct vs. Vicarious Liability

Indian criminal law maintains a clear separation between direct and vicarious liability. This distinction is central to understanding an admin's responsibilities. The Supreme Court, in cases like Sham Sunder v. State of Haryana, has consistently held that vicarious liability in criminal law can only be imposed by a specific statute, not by judicial interpretation. Since neither the Indian Penal Code nor the IT Act contains such a provision for social media admins, the basis for vicarious liability does not exist.

The Scale of Criminal Liability

Direct Liability

An admin is fully responsible for any unlawful content they personally create, post, or forward. This is undisputed.

Vicarious Liability

Holding an admin responsible for a member's post. In criminal law, this is not permitted without a specific law from Parliament.

III. Judicial Scrutiny: A Consensus Among High Courts

Over the past few years, a series of landmark judgments from various High Courts have formed a clear and consistent legal position on admin liability.

Pathways to Admin Liability: A High Bar

This chart illustrates the exceptionally high evidentiary burden required to hold an admin liable for a member's post, compared to their direct liability.

The "Common Intention" Test

The landmark Bombay High Court ruling in Kishor v. State of Maharashtra established the "common intention" test. An admin can only be held liable for a member's post if the prosecution can prove a pre-arranged plan or conspiracy. The court noted that an admin cannot have "advance knowledge of the criminal acts of the member."

"...cannot be held vicariously liable... unless it is shown that there was common intention or pre-arranged plan acting in concert..."

Landmark Judicial Pronouncements

| Case Name & Citation | Court | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Kishor v. State of Maharashtra (2021) | Bombay High Court | Established the "common intention" test; no vicarious liability without a pre-arranged plan. |

| Ashish Bhalla v. Suresh Chawdhary (2016) | Delhi High Court | Admin liability is like holding a newsprint maker liable for defamatory content. |

| Manual v. State of Kerala (2022) | Admin is not an "intermediary" under the IT Act; vicarious liability requires a statute. | |

| R. Rajendran v. The Inspector of Police (2021) | Madras High Court | Followed Bombay HC precedent, ordering admin's name removed from FIR. |

IV. Status under the Information Technology Act, 2000

A pivotal question is whether an admin qualifies as an "intermediary" under the IT Act. The judiciary has decisively concluded that they do not. An admin does not receive, store, or transmit messages "on behalf of" other members; each member posts on their own behalf using the service provided by WhatsApp Inc., the actual intermediary.

A Double-Edged Sword

Because an admin is not an intermediary, they are shielded from complex due diligence rules. However, this also means they cannot claim "safe harbour" immunity under Section 79 of the IT Act, leaving them fully exposed to direct liability for their own actions.

V. Potential Grounds for Direct Liability: Navigating the IPC & IT Act

While shielded from vicarious liability, an admin is fully accountable for their own actions. The primary legal avenue for implicating an admin in a member's post is through the law of abetment under Section 107 of the Indian Penal Code. This requires proving instigation, conspiracy, or intentional aid. The "common intention" test is a judicial restatement of these requirements, focusing on mens rea (a guilty mind). Proving a pre-arranged plan is exceptionally difficult, which is how the judiciary protects admins from frivolous prosecution while acknowledging a theoretical path to liability.

Applicable Penal Provisions and Administrator Liability

| Statute | Section | Offence Description | Potential Admin Liability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | 153A | Promoting enmity between groups (hate speech). | Direct liability if admin posts; vicarious only if 'common intention' is proven. |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | 499/500 | Defamation. | Direct liability if admin posts; vicarious only if 'common intention' is proven. |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | 505 | Statements conducing to public mischief (rumours). | Direct liability if admin posts; vicarious only if 'common intention' is proven. |

| IT Act, 2000 | 67 | Publishing or transmitting obscene material. | Direct liability if admin posts; vicarious only if 'common intention' is proven. |

VI. The Shifting Digital Landscape: Impact of the IT Rules, 2021

The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, have introduced new obligations, primarily on "significant social media intermediaries" (SSMIs) like WhatsApp. The most contentious is the "first originator" traceability mandate, which requires platforms to identify the origin of a message under a court order. WhatsApp has challenged this rule, arguing it would break end-to-end encryption and violate user privacy.

The Chilling Effect of Traceability

This creates a new risk vector. While an admin may be safe from vicarious liability for what a member posts, the group becomes more vulnerable to surveillance. If an admin forwards a message later deemed unlawful, they could be identified as the "first originator" in that chain, facing direct liability. This increased risk of being traced is likely to have a "chilling effect" on free expression within private groups.

VII. The Enforcement Gap: When Law on the Books Meets Law on the Ground

Despite the clarity provided by the higher judiciary, a significant "enforcement gap" persists. This refers to the disconnect between the well-reasoned legal principles established by High Courts and the on-ground practices of law enforcement agencies, which have sometimes continued to arrest administrators based on their status alone.

Risk of Harassment and Wrongful Prosecution

This disconnect creates a climate of fear and uncertainty. An admin's de jure legal protection does not guarantee de facto safety from investigation, harassment, and the financial burden of litigation. This can lead to a "chilling effect" on free speech, as individuals may self-censor or shut down groups to avoid wrongful prosecution. There is an urgent need for systematic training of police authorities to align their actions with the law laid down by the courts.

Analysis of Conflicting or Nuanced Rulings

While the consensus is strong, it is not entirely monolithic. A ruling by the Madhya Pradesh High Court appeared to take a divergent view, holding that an admin, even a default one, could be held accountable because their continued presence during the circulation of objectionable material established a prima facie case of liability. This judgment is best understood as an outlier that deviates from the well-reasoned and widely accepted principles established by other High Courts. It places emphasis on passive presence rather than the active intent required by the "common intention" test and has not been widely followed.

VIII. Visualizing Liability: A Decision Flowchart

To simplify the complex legal tests discussed, the following flowchart illustrates the decision-making process for determining an administrator's potential liability when a member posts objectionable content.

Start: Objectionable Content Posted by a Member

Decision Point 1

Was the content posted or forwarded by the Admin personally?

Outcome

Admin faces Direct Liability for their own actions.

Decision Point 2

Is there evidence of a "Common Intention" or "Pre-arranged Plan" with the member?

Outcome

Admin MAY face liability for abetment/conspiracy (High evidentiary burden).

Outcome

Admin is NOT LIABLE for the member's post. Taking reactive measures further strengthens this position.

IX. Best Practices for Responsible Group Administration

While the law protects admins from the actions of others, proactive governance is the best strategy to mitigate legal risks and demonstrate an intent to maintain a lawful group environment.

Proactive Measures

-

Establish a Group Charter: Pin clear rules prohibiting illegal content.

-

Vet Members: Avoid adding unknown individuals to sensitive groups.

-

Inform and Remind: Periodically post reminders about group rules.

Reactive Measures

-

Delete & Disassociate: Immediately delete objectionable messages for everyone.

-

Warn & Remove: Issue a public warning and remove the offending member if necessary.

-

Report Serious Crimes: Report illegal content to WhatsApp and law enforcement.

Documentation & Reporting

-

Maintain Records: Take screenshots of offensive posts and the corrective actions you took (warnings, removal).

-

Report to Authorities: For serious crimes, report the user to WhatsApp and consider filing a complaint with the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal.

Conclusion: A Clear Path Forward

The legal position is clear: a WhatsApp admin's liability hinges on their own actions and intent, not their title. While the judiciary provides a strong shield against vicarious liability, a dangerous "enforcement gap" with on-ground policing remains a concern. The path to safety for administrators lies in proactive governance, responsible conduct, and a clear understanding that while they are not their members' keepers, they remain the masters of their own actions.