Executing an adoption deed through a testamentary guardian seems like a straightforward process under Hindu personal law. But what happens when the child is an orphan? This is where the legal framework in India becomes complex, pitting the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (HAMA) against the overriding mandate of the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015 (JJ Act). This in-depth analysis breaks down the critical legal distinctions, explains the exclusive role of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) and CARA in orphan adoptions, and outlines the severe legal consequences—from voided inheritance rights to potential criminal liability—of relying on an invalid deed. We will guide you through the correct, legally sound procedure to ensure your adoption is valid and secure.

Evaakil.com

Legal Validation of an Adoption Deed by a Testamentary Guardian in India

An In-depth Analysis for October 2025

Decoding the Deed: A Clause-by-Clause Breakdown

The submitted adoption deed was drafted with careful attention to the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956. Let's break down its key components to understand its intent and where it aligns with HAMA.

The Parties Involved

- Adoptive Father: The individual seeking to adopt.

- The Guardian: A "Testamentary Guardian" appointed by the deceased father's will. This is a key element that invokes Section 9 of HAMA.

The "Whereas" Recitals

These clauses lay the factual groundwork for the adoption under HAMA:

- Asserts no pre-existing son (fulfilling HAMA Sec 11).

- Confirms natural parents are deceased.

- Notes the adoptive father's wife's consent (HAMA Sec 7).

- Crucially: Mentions prior permission from a District Judge for the guardian to give the child in adoption, as mandated by HAMA Section 9(4).

The Declaration & Ceremony

The deed's core purpose is to declare the adoption complete. It specifically references the "ceremony of giving and taking," which is the heart of a customary Hindu adoption.

- The Physical Act: This refers to the actual, physical handing over of the child by the guardian and acceptance by the adoptive father.

- Manifestation of Intent: The ceremony is the clearest evidence of the intent to transfer the child from their birth family to the adoptive family.

- Mandatory Condition: Under HAMA Section 11(vi), this physical act is an essential condition for a valid adoption. The deed serves to record this vital event.

Critical Oversight: While the deed is meticulously crafted for HAMA, its entire foundation is shaken by the child's orphan status, which triggers a different, overriding law. This highlights a common pitfall: focusing on one personal law while ignoring a superseding secular statute.

The Guardian's Power to Act: A HAMA Deep Dive

The deed's reliance on a "Testamentary Guardian" is a direct invocation of Section 9 of HAMA. Understanding this guardian's specific legal capacity is crucial to grasping the deed's intended legal basis.

Who Can Give a Child in Adoption?

HAMA outlines a strict hierarchy for who holds the authority to give a child away:

- The Father: The primary authority, but only with the mother's consent.

- The Mother: If the father is deceased, has renounced the world, or has been declared of unsound mind.

- The Guardian: This is where the current case falls. A guardian can only act if both parents are deceased or incapacitated.

The Guardian's Critical Limitation

Crucially, Section 9(4) of HAMA places a significant check on a guardian's power. They cannot give a child in adoption without the prior permission of a court. The court's primary consideration is the child's welfare. The deed correctly recites that this permission was obtained, showing procedural awareness of HAMA's requirements.

Section 9, HAMA (1956)

This section grants testamentary guardians the power to give a child in adoption, but strictly conditions it on court approval to safeguard the child's best interests.

The Legal Crossroads: HAMA vs. The JJ Act

The most critical legal question is not whether the deed follows HAMA, but whether HAMA is the correct law to begin with. Here, the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, asserts its dominance.

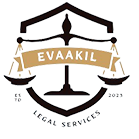

Which Legal Path Applies? A Comparative View

The child's status as an orphan is the determining factor. This graphic compares the two legal frameworks side-by-side.

Via Personal Law (HAMA)

Triggered when a child is given by biological parents.

Governing Law: Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956

Key Actor: Parents / Testamentary Guardian (with court nod)

Legal Instrument: Adoption Deed

Status: Legally vulnerable and incorrect for an orphan child.

Via Secular Law (JJ Act)

Triggered when a child is an orphan, abandoned, or surrendered.

Governing Law: Juvenile Justice Act, 2015

Key Actor: Child Welfare Committee & Court

Legal Instrument: Final Adoption Order from Court

Status: The only legally secure and mandatory path for this case.

The Overriding Mandate: Section 1(4) of the JJ Act contains a non-obstante clause, giving it precedence over any other law in force concerning children in need of care and protection. For a complete overview of both legal frameworks, see our comprehensive HAMA & JJ Act Guide.

The Apex Body: Understanding CARA's Role

The JJ Act pathway is not just a legal theory; it is a structured process managed by a central authority. Any discussion of modern adoption in India is incomplete without understanding the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA).

What is CARA?

CARA is a statutory body under the Ministry of Women & Child Development. It functions as the nodal body for the adoption of Indian children and is mandated to monitor and regulate both in-country and inter-country adoptions.

Why CARA is Mandatory for Orphans

Under the JJ Act, every orphan, abandoned, or surrendered child must be brought into the CARA system. This ensures:

- Legally Free Status: The Child Welfare Committee (CWC) legally declares the child free for adoption.

- Transparency: Prospective parents register on the CARINGS portal, ensuring a transparent, regulated process.

- Child Protection: The system includes background checks, home studies, and post-adoption follow-ups to protect the child's welfare.

Key Takeaway: Bypassing CARA and the CWC through a private adoption deed for an orphan child is not a mere procedural shortcut; it is a fundamental legal error that renders the adoption invalid from the outset.

Procedural Imperatives & Evidentiary Value

Legal validity hinges on following the correct procedure. The choice of document—an adoption deed versus a court order—is not a matter of preference but a mandate of the applicable law.

Adoption Deed (Under HAMA)

This is a private document executed between the parties. While registration is not mandatory for validity, it is highly recommended.

Key Point:

An adoption deed is a record of an event that has already taken place (the ceremony of giving and taking). It does not create the adoption itself.

Adoption Order (Under JJ Act)

This is a formal decree issued by a court of competent jurisdiction (District Magistrate, as per recent amendments).

Key Point:

The court order is what legally creates the status of adoption. It is the culmination of a state-regulated process and is the only valid method for adopting an orphan.

Evidentiary Value & The Burden of Proof

Section 16 of HAMA gives significant weight to a registered adoption deed, but it's a presumption that can be challenged.

The chart below visualizes the legal presumption of validity. A registered deed shifts the burden of proof to the person challenging the adoption.

Legal Format Specimen: Deed of Adoption (HAMA Framework)

Below is a general template for a Deed of Adoption as executed under the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956. Disclaimer: This format is for informational purposes only and is inapplicable for adopting an orphan, abandoned, or surrendered child, which must be done via the JJ Act. Always consult a qualified lawyer for legal advice.

DEED OF ADOPTION

THIS DEED OF ADOPTION is made and entered into at [City] on this [Date] day of [Month], [Year].

BETWEEN:

Sri/Smt. [Name of Adoptive Father/Mother], son/daughter/wife of [Father's/Husband's Name], aged about [Age] years, residing at [Full Address].

(Hereinafter referred to as the "ADOPTIVE PARENT", which expression shall unless repugnant to the context or meaning thereof be deemed to mean and include his/her legal heirs, executors, administrators and assigns) of the FIRST PART.

AND:

Sri. [Name of Guardian], son of [Father's Name], aged about [Age] years, residing at [Full Address], acting as the testamentary guardian of the minor child.

(Hereinafter referred to as the "GUARDIAN") of the SECOND PART.

WHEREAS:

- The Adoptive Parent, being a Hindu, has no son, son's son, or son's son's son living at this time and is desirous of adopting a son.

- The natural father and mother of the minor child, [Name of Child], born on [Child's Date of Birth], are deceased.

- The natural father, by his last will and testament dated [Date of Will], appointed the Guardian to be the testamentary guardian of the said minor child.

- The Guardian had applied to the District Judge of [District Name] for permission to give the said child in adoption, and permission was granted by Order dated [Date of Court Order].

- The ceremony of giving and taking the child in adoption has been duly performed on [Date of Ceremony] along with other religious ceremonies customary to the parties.

- The parties consider it expedient to execute this Deed of Adoption to serve as an authentic record of the said adoption.

NOW, THIS DEED WITNESSETH AS FOLLOWS:

- Declaration of Adoption: The parties hereby declare that the Adoptive Parent has adopted the said child, [Name of Child], as his/her son/daughter from the [Date of Ceremony], on which day the ceremony of giving and taking was performed.

- Legal Rights and Liabilities: The said child is now transferred to the family of the Adoptive Parent and shall have all the legal rights and liabilities of a natural-born child of the Adoptive Parent from the date of adoption.

- Maintenance and Upbringing: The Adoptive Parent shall be liable for the maintenance, education, and all other expenses of the adopted child in accordance with his/her status.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties have executed this Deed of Adoption on the date first above written.

_________________________

(Signature of ADOPTIVE PARENT)

_________________________

(Signature of GUARDIAN)

WITNESSES:

-

Name: ____________________

Address: __________________

Signature: ________________

-

Name: ____________________

Address: __________________

Signature: ________________

The Domino Effect: Legal Consequences of an Invalid Adoption

An adoption deed that is not legally valid is more than just a flawed document; it creates a cascade of severe legal and personal problems for both the child and the adoptive parents. The risks are profound.

Inheritance Rights Voided

The child has no legal right to inherit property from the adoptive parents as a Class I heir. They would be treated as a stranger to the family in matters of succession.

Legal Parentage Unrecognized

The adoptive parents are not recognized as the legal parents. This affects school admissions, official documents (like passports), and medical consent.

Maintenance Claims Denied

The child cannot legally claim maintenance from the adoptive parents, and conversely, the parents cannot claim maintenance from the child in their old age.

Emotional and Social Turmoil

The uncertainty and potential for legal challenges can cause immense emotional distress and social stigma for the family and child.

Vulnerability to Challenges

The adoption can be challenged at any time by other relatives, especially in property disputes, potentially uprooting the child's life.

Criminal Liability

Section 80 of the JJ Act criminalizes offering or receiving a child outside the prescribed procedures, potentially leading to imprisonment.

A Note on Historical Doctrine: 'Relation Back'

For those interested in the evolution of Hindu adoption law, the "doctrine of relation back" is a fascinating concept that was significantly altered by the HAMA, 1956.

Before 1956 (Old Law)

Under the old shastric law, an adoption by a widow was deemed to be for her deceased husband. The adopted son was considered to have been adopted on the date of the adoptive father's death, not the actual date of adoption. His rights to property would "relate back" to this earlier date, allowing him to divest estates that had already been vested in other heirs.

After 1956 (HAMA)

HAMA abolished this complicated and disruptive legal fiction. Under Section 12, an adopted child is deemed to be the child of the adoptive parent from the date of the adoption. The adoption does not relate back; it creates a new legal reality from that moment forward and cannot divest any property that has already vested in any person before the adoption.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

While a registered deed carries a strong presumption of validity (Section 16, HAMA), an unregistered deed is not automatically void. However, the burden of proving that a valid adoption took place (including the giving and taking ceremony) falls heavily on the person claiming the adoption. It is a much weaker and more vulnerable position.

A testamentary guardian only gains authority after the death of the person who appointed them (the testator). If the biological parents are alive, they are the natural guardians and hold the primary right to give the child in adoption. A testamentary guardian's role would not be triggered in that scenario.

The deed itself cannot be "fixed." The only way to create a legally secure adoption for an orphan is to follow the JJ Act procedure. This would involve approaching the District Child Protection Unit (DCPU) or a Specialised Adoption Agency (SAA) to have the child formally brought into the system, declared legally free for adoption by the CWC, and then having a court issue a final, legally binding adoption order.

Further Reading & Resources

For a broader understanding of adoption laws in India, explore our other comprehensive guides:

Child Adoption Process in India 2025: HAMA & JJ Act Guide

A detailed walkthrough of the procedures, eligibility, and legal nuances under both major adoption laws in India.

Adopting from India: A Foreigner's Guide

Specific guidance for foreign nationals and NRIs on navigating the inter-country adoption process governed by CARA.

Final Verdict & Corrective Legal Pathway

Based on the analysis, the adoption deed is invalid for its intended purpose. The only legally sound path forward is through the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015. Here is a checklist of the mandatory corrective steps.